Building the US Naval Radio Station in Haʻikū Valley was one of the most complex and perplexing jobs of the Pacific offensive. The facility was classified top secret and there was no discussion with the Army or the operating committee of the Navy. There was no real model to follow for engineering construction, and the terrain was extremely rugged and often dangerous to work in.

Along with the shortage of workers and materials there was also an atmosphere of heightened stress in Hawaii following the trauma of the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. The community was struggling with the tension of living under martial law, including black outs, and curfews. Barbed-wire was strung along the beaches as a vivid reminder of how vulnerable the islands were to attack.

Barbed wire topping the beach at Waikiki. Image courtesy of the Bishop Museum/Desoto Brown

"One of the fabulous tales of the war now being made public concerns the great navy radio-sending station built in the utmost secrecy in Haiku valley, windward Oahu, starting in 1942..."

Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 25 Oct 1946

Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 25 oct 1946. Original newspaper clippings courtesy of the archives of John Flanigan, FHS board member emeritus

Construction of the top secret US Naval Radio Station in Ha'ikū Valley began in 1942. It was built using the topography of the surrounding cliffs, the most innovative technology of the time, and sheer determination to create an antennae system that reached almost 3,000 feet across the Valley. Once operational, the low frequency radio system at Ha'ikū could send messages to submarines as far away as Tokyo Harbor. The groundbreaking design and construction of the Naval Radio Station is testament to the courage and ingenuity of both military and civilian personnel under the pressure of war.

Constructing the Stairs

The valley, however, was covered with dense vegetation and had large lava rocks. Huge twisted hau trees were tightly knit throughout the valley. Axes were used to chop through the hau trees as the first expeditions were made though the valley (Woodbury, 1946:350).

Beyond clearing the valley, the largest problem facing the construction of the radio station was finding a way to send men to the top of the cliffs. The cliffs that semi-encircle the valley range between 1,800 and 2,850 feet. In many places the cliffs rise almost vertically. To further add to the problems of scaling was the fact that the dirt was often either crumbly lava or was muddy and unstable from the high amount of rain and fog.

.jpg)

The Ha'ikū Stairs were as essential part of the pioneering long-range low-frequency US Naval Radio Station that was built on O'ahu beginning in 1942

The High-Scalers of Ha'ikū

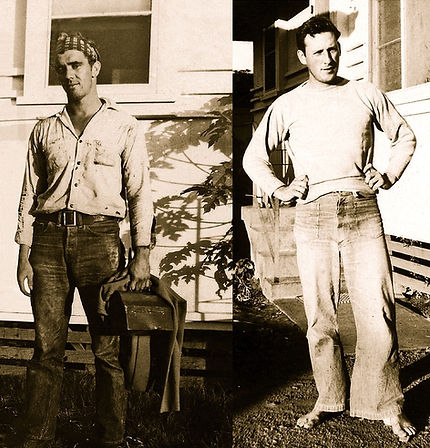

The contractors had considered sending back to the mainland for professional high-scalers when it was brought to their attention that two such high-scalers were working on another tough military project in nearby Red Hill. The two men, Bill Adams and Louis Otto, under the leadership of rigger Ray Cotherman, were known for their fierce determination and courage in conquering the heights. They began their climb up the steep slopes with one coil of rope, a rock pick-sledge hammer, and some three foot steel pins (Woodbury, 1946:356).

The story of their ascent and the construction that they opened the door to has been documented in magazines such as Reader’s Digest, and in David O. Woodbury’s book, Builders for Battle (1946:356):

"The climbers began up the south, or Pali, side of the valley. The two men worked their way up the steep rock by driving in one spike, standing on it and driving in another, attaching the rope to that spike and then pulling themselves up to drive in another spike. When the spikes were used up for the day they returned to the bottom and began again the next day. It took Adams and Otto 21 days before they reached the top. What the two found was that the top of the cliffs were, in effect, a ‘razor top’. Nowhere was the top more than 12 feet wide and in most areas it was 4 to 5 feet wide."

.jpg)

It took Bill Adams and Louis Otto 21 days to scale 2,800 feet to the peak of Pu'u Keahiakahoe on Ha'ikū Valley's eastern wall

The Naval Radio Station under Construction, circa 1943

Certain portions of the work were later completed by construction battalion forces including, “installation of the 600-kw diesel standby generator in the bombproof transmitter building, installation of several poles on the transmitter building on the Pali summit, and installation of a short length of underground cable” (U.S. Dept. Navy, A-829; 1944).

The US Naval Radio station at Haʻikū Valley satisfied two requirements of the war. It allowed for long range transmission and was built in a position that allowed for excellent natural protection. “The Haiku Radio project was completed in December of 1943 and over the 200 KW Alexanderson Alternator at Haiku messages to merchant ships, weather reports to naval ships and despatches to submarines were broadcast” (Honolulu Nav Comm Sta, 1960:5).

Historic images on this page courtesy of Dave Jessup, Ted Urquhart, and John Flanigan

Building for War: Contractors, Pacific Naval Air Bases

How to make this low frequency radio system become reality was one of the most complicated jobs in the Pacific during the war. The project was one of hundreds that were completed under the coordination and leadership of the Pacific Naval Air Base. The PNAB was initiated in the 1930s as turmoil was mounting in the Pacific. At that time, the mood of America was one of caution. People were very hesitant to become involved in another war, particularly if America was not directly involved. However, in 1938, there were also many officers and political leaders that sensed the seriousness of the rising turmoil in China and the growing interest of the Japanese in the Pacific, including Hawai'i. These individuals, including Charles Edison as the Assistant Secretary of the Navy and Rear Admiral Ben Moreell, the head of the Bureau of Yards and Docks, met with President Roosevelt. Working towards the same goal, they slowly and stubbornly inched towards a proposal for Pacific Naval Bases (Woodbury, 1946: 65).

At this point in time the proposal for the Pacific Naval Air Bases was being limited to defensive measures. In January of 1939 the Naval Affairs Committee opened hearings on the specifics of the proposed new Naval Bases. During this hearing Admiral Moreell laid out the exact method that would be used in building the bases. The Admiral proposed:

” . . . the vital issue of using private contractors to do the work in the pacific. There would be no bidding on the island contracts. The Navy would choose the contractors it believed competent to do pioneering work under stress of emergency, then pay them on a cost-plus-fixed fee basis. This would be the first time that the Government had ever used this method on a big job” (Woodbury, 1946: 52).

This innovation constituted the Contractors, Pacific Naval Air Base. In the hearings of 1939 were stated several points that convinced skeptics of the decision to use this system of CPNAB. First, that private contractors would be used because the use of civil service engineers was too slow. Second, the contracts were awarded to large firms because small ones did not have the experience or talent for this large scale operation. Lastly, contracts should be paid a fixed fee instead of the conventional percentage of cost because it does not benefit the contractor to spend money but instead rewards him for not spending money (Woodbury, 1946:59). On May 25th, 1939 Congress passed an appropriation bill providing 63 million dollars for Naval Air Bases. In the near future the unique and innovative organization of the CPNAB set forth by Admiral Moreell would prove indispensable for expeditious construction in Hawai'i after the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor (Woodbury, 1946:55).

Alexanderson with his revolutionary 200 kilowatt Alexanderson Alternator at the Naval Radio Station at Haiku

A naval engineer attends to one of the antennae

on the west side of the transmitter building

at the Naval Radio Station at Haiku

This cable car took workers from the floor of Haʻikū Valley to the peak some 2,800 feet above. During the radio station’s operation, most workers preferred to ride the car to the upper hoist house than climb what was originally called the Haiku Ladder

Over one hundred firms applied to be the Contractors used for the Pacific Naval Bases. After much deliberation and intensive screening three companies were determined to be the strongest competitors having knowledge, experience, and imagination. The original contractors were Turner Construction Company of New York, the Raymond Pile Company of New York, and the Hawaiian Dredging Company. On August 9th the contract (No y-3550) was approved and the Contractors began work. Logistics were quickly decided upon and offices began to function. One of the first tasks was building the Operation Office in Alameda. This office would be responsible for coordinating all of the purchasing and shipping of supplies (Woodbury, 1946:68).